Plastic Nests

In 2023, the University of Birmingham posted a blog called “Man-made materials in nests can bring both risks and benefit for birds”. The headline alone elicited a slow inhale, a second read, and a bundle of questions. Evidently, this isn't a conventional story of plastic pollution wreaking havoc. This is a different kind of chaos - a tale of urban-nature entwinement with myriad implications for how we consider our interrelations with other species and the places they live, recharge their energies, and raise their families.

A nest is generally defined as a shelter or structure built by birds, and some other creatures, in which they lay their eggs and care for their young. Some people use the word nest, leaning on its association with safety and warmth, as an endearing term for their human homes. To nest can also mean to fit inside. Writing this, I wondered about the difference (if there is one) between a nest and a roost. Apparently, a nest is usually a seasonal home, built for the specific purpose of bringing up the next generation. A roost is a place where birds rest and sleep, commonly used all year round. Doing this surface level research, I realise just how little I know about the places other animals make homes. Reading the aforementioned study about the many impacts of man-made materials being incorporated in nests made that even clearer.

The study being referenced in the Birmingham University blog is featured in the Royal Societies four part collection of investigations titled, “The evolutionary ecology of nests: a cross-taxon approach”. This impressively varied set of investigations is borne from a “burgeoning amount of interest in nests over the past decade” (Mainwaring, 2023). It explores the varied function of nests, their evolution over time, the ‘communal’ construction of nests in harsh environments, and (most relevant to this story) nests in the anthropocene.

A team of researchers discovered 176 bird species found to be integrating fabricated materials such as plastics in their nests. The scale of the research and triangulation of data across so many species and places was possible thanks to increasingly sophisticated analytic, computational, and nest scanning technologies. This marks a watershed moment in the scientific world of nest-related research: “To date, many studies examining nests have focused on single species, and topics have been treated in an isolated manner, meaning that the full extent of the inter-disciplinary nature of the field has not been synthesized”.

Compiling and cross-comparing data from nests all over the world, the researchers found that a broad range of items, from plastic fishing nets, to food packaging, and cigarette butts, may become part of a bird nest. This is a tale of entanglement that pulls listeners in closely and quickly. Other fabricated materials initially intended to deter birds have also been found woven into their nests. There is something uniquely intriguing about this study. It shatters the widely held assumptions that, a) our human lives, our waste, exists in isolation from the rest of nature, and b) that wildlife can only ever be harmed, never helped, by our detritus. To fall wholly for the latter would be to underestimate the resilience of nature, the creativity of animal minds, and the oddities of urban-nature entanglement. The study proved that the phenomenon of birds constructing nests with artificial materials isn't a freak instance, in many places, this is a real and lasting part of life now (Jagiello et al., 2023).

By dissecting nests which contain various plastic scraps and components, scientists have used printed expiration dates to approximate the time of manufacturing. This makes the nests obscure artefacts of our present era of over consumption and inability to effectively manage the lifecycle of disposable packaging. Most readers will have heard some version of the message, ‘we’re drowning in plastic’, countless times. The plastic nests story, however, plucks the same chord as the cocaine shrimp at the heart of the last pollen project article. It enables deeper, more curious engagement with the bigger picture by entering through a narrow, perhaps unexpected, in-point. People genuinely want to hear more.

Much like the drugs in the shrimp, more time is needed to understand the long term effects of plastic in nests. What has been observed, thus far, is that using macro plastics such as near-full pieces of packaging in nests could alter the behaviour of species, such as the wetland-dwelling common coot, who may begin to reuse nests for multiple years as a result of these relatively new plastic elements. Conventionally, these birds use natural materials prone to rapid decay meaning that annual nest repair, renovation, and reuse hasn't been on the cards.

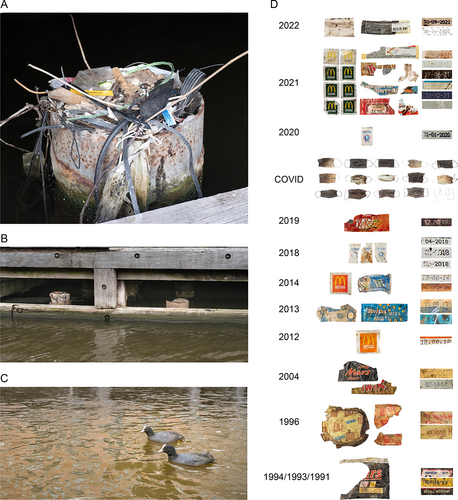

[image credit: Hiemstra, A., Gravendeel, B. and Schilthuizen, M. (2025). Birds documenting the Anthropocene: Stratigraphy of plastic in urban bird nests. Ecology, 106(2). doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.70010.]

A thematically related study was published in February 2025 titled ‘Birds documenting the Anthropocene: Stratigraphy of plastic in urban bird nests’. The paper reports that “Plastic may be used as a global marker for the Anthropocene, which allows plastic items to be used as “index fossils” to date with accuracy sediment layers within the Anthropocene epoch” (Hiemestra et al., 2025).

The study spotlights a unique nest found beneath the Oude Turfmarkt dock in Amsterdam. This nest was constructed on an unused foundation pile, in a 20cm deep hollow space created by the shell of a slightly longer metal pipe around the pile. The researchers “observed recent top layers of facemasks and the deepest layers of nest material showed plastic dating back to the early 1990s”. The image to the left shows an assortment of the 635 artificial items found when the nest was deconstructed. The facemasks signal the COVID era, present in high numbers in the 2019 - 2020 layers of the Oude Turfmarkt nest. McDonalds branded plastics are a consistent feature in every layer of the nest - a whole story in itself.

Undergirding the intrigue, this research, of course, has a dismal aspect. It's not good that we’re failing to dispose of these materials, and they no doubt cause disruption and harm to the birds who use them in nests, but that isn't the real focus of this article

Rather, the point being explored here is that there is an untapped power in stories that highlight the breakage and mutation of bonds between humans and the rest of nature. Dismembering the nests, separating its parts, and questioning their origins opens a door to reconnecting with nature, and remembering that wherever we are, we never exist alone as a species and always live in entanglement with others.

A nest is a story: an amalgamation of past and present, twisted, pieced, and twined together in hopes to safely raise a future generation of (in this instance) feathered beings.

A nest, from my still limited understanding, is a site of care. The burgeoning scientific interest in their composition, including plastics and other fabricated materials, coupled with growing technologies and data-sharing networks, creates a powerful narrative opportunity. What are the nests, their builders, and their residents, telling us? How will we respond?

Telling tales, like the cocaine shrimp and plastic nests, of urban nature hybridity, unlocks layers of emotion and curiosity that generate useful ripple effects. As time goes by, we hope pollen becomes a site to surface, save, and share stories in this vein for others to encounter. As news rolls out about the Global Plastics Treaty, perhaps these are the kinds of stories we need more of to root concerted action in gut feelings, curiosity, and the messy realities of life in the 2020’s.

If you have a layer to add, or a new story to tell, we welcome you to reach out.

Written by Lucy Gavaghan

References

Hiemstra, A., Gravendeel, B. and Schilthuizen, M. (2025). Birds documenting the Anthropocene: Stratigraphy of plastic in urban bird nests. Ecology, 106(2). doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.70010.

Mainwaring, M.C., Mary Caswell Stoddard, Barber, I., Deeming, D.C. and Hauber, M.E. (2023). The evolutionary ecology of nests: a cross-taxon approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 378(1884). doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0136

Jagiello, Z., Reynolds, S.F., Nagy, J., Mainwaring, M.C. and Juan Diego Ibáñez-Álamo (2023). Why do some bird species incorporate more anthropogenic materials into their nests than others? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 378(1884). doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0156.